Now we shall address how to solve nonlinear PDEs in FEniCS. Our sample PDE for implementation is taken as a nonlinear Poisson equation:

The coefficient  makes the equation nonlinear (unless

makes the equation nonlinear (unless  is constant in

is constant in  ).

).

To be able to easily verify our implementation,

we choose the domain,  ,

,  , and the boundary

conditions such that we have

a simple, exact solution

, and the boundary

conditions such that we have

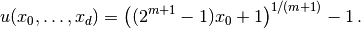

a simple, exact solution  . Let

. Let

be the unit hypercube

be the unit hypercube ![[0, 1]^d](_images/math/0ee1e007f47139a819af6241b0bdd8fee169e767.png) in

in  dimensions,

dimensions,  ,

,  ,

,  for

for  ,

,  for

for  , and

, and  at all other boundaries

at all other boundaries

and

and  ,

,  . The coordinates are now represented by

the symbols

. The coordinates are now represented by

the symbols  . The exact solution is then

. The exact solution is then

We refer to the section Parameterizing the Number of Space Dimensions for details on formulating a PDE

problem in  space dimensions.

space dimensions.

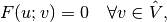

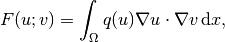

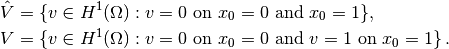

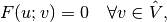

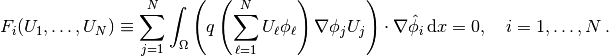

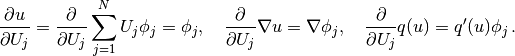

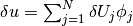

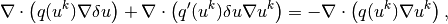

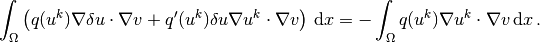

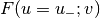

The variational formulation of our model problem reads:

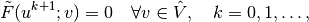

Find  such that

such that

(1)

where

(2)

and

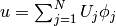

The discrete problem arises as usual by restricting  and

and  to a

pair of discrete spaces. As usual, we omit any subscript on discrete

spaces and simply say

to a

pair of discrete spaces. As usual, we omit any subscript on discrete

spaces and simply say  and

and  are chosen finite dimensional

according to some mesh with some element type.

Similarly, we let

are chosen finite dimensional

according to some mesh with some element type.

Similarly, we let  be the discrete solution and use

be the discrete solution and use  for

the exact solution if it becomes necessary to distinguish between the two.

for

the exact solution if it becomes necessary to distinguish between the two.

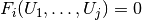

The discrete nonlinear problem is then wirtten as: find  such that

such that

(3)

with  . Since

. Since  is a nonlinear function

of

is a nonlinear function

of  , the variational statement gives rise to a system of

nonlinear algebraic equations.

[[[

FEniCS can be used in alternative ways for solving a nonlinear PDE

problem. We shall in the following subsections go through four

solution strategies:

, the variational statement gives rise to a system of

nonlinear algebraic equations.

[[[

FEniCS can be used in alternative ways for solving a nonlinear PDE

problem. We shall in the following subsections go through four

solution strategies:

- a simple Picard-type iteration,

- a Newton method at the algebraic level,

- a Newton method at the PDE level, and

- an automatic approach where FEniCS attacks the nonlinear variational problem directly.

The “black box” strategy 4 is definitely the simplest one from a programmer’s point of view, but the others give more manual control of the solution process for nonlinear equations (which also has some pedagogical advantages, especially for newcomers to nonlinear finite element problems).

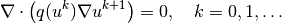

Picard iteration is an easy way of handling nonlinear PDEs: we simply

use a known, previous solution in the nonlinear terms so that these

terms become linear in the unknown  . The strategy is also known as

the method of successive substitutions.

For our particular problem,

we use a known, previous solution in the coefficient

. The strategy is also known as

the method of successive substitutions.

For our particular problem,

we use a known, previous solution in the coefficient  .

More precisely, given a solution

.

More precisely, given a solution  from iteration

from iteration  , we seek a

new (hopefully improved) solution

, we seek a

new (hopefully improved) solution  in iteration

in iteration  such

that

such

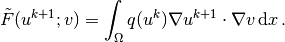

that  solves the linear problem,

solves the linear problem,

(4)

The iterations require an initial guess  .

The hope is that

.

The hope is that  as

as  , and that

, and that

is sufficiently close to the exact

solution

is sufficiently close to the exact

solution  of the discrete problem after just a few iterations.

of the discrete problem after just a few iterations.

We can easily formulate a variational problem for  from

the last equation.

Equivalently, we can approximate

from

the last equation.

Equivalently, we can approximate  by

by  in

in

to obtain the same linear variational problem.

In both cases, the problem consists of seeking

to obtain the same linear variational problem.

In both cases, the problem consists of seeking

such that

such that

(5)

with

(6)

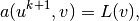

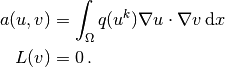

Since this is a linear problem in the unknown  , we can equivalently

use the formulation

, we can equivalently

use the formulation

with

The iterations can be stopped when  , where

, where  is a small tolerance, say

is a small tolerance, say  , or

when the number of iterations exceed some critical limit. The latter

case will pick up divergence of the method or unacceptable slow

convergence.

, or

when the number of iterations exceed some critical limit. The latter

case will pick up divergence of the method or unacceptable slow

convergence.

In the solution algorithm we only need to store  and

and  ,

called u_k and u in the code below.

The algorithm can then be expressed as follows:

,

called u_k and u in the code below.

The algorithm can then be expressed as follows:

def q(u):

return (1+u)**m

# Define variational problem for Picard iteration

u = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

u_k = interpolate(Constant(0.0), V) # previous (known) u

a = inner(q(u_k)*grad(u), grad(v))*dx

f = Constant(0.0)

L = f*v*dx

# Picard iterations

u = Function(V) # new unknown function

eps = 1.0 # error measure ||u-u_k||

tol = 1.0E-5 # tolerance

iter = 0 # iteration counter

maxiter = 25 # max no of iterations allowed

while eps > tol and iter < maxiter:

iter += 1

solve(a == L, u, bcs)

diff = u.vector().array() - u_k.vector().array()

eps = numpy.linalg.norm(diff, ord=numpy.Inf)

print 'iter=%d: norm=%g' % (iter, eps)

u_k.assign(u) # update for next iteration

We need to define the previous solution in the iterations, u_k, as a finite element function so that u_k can be updated with u at the end of the loop. We may create the initial Function u_k by interpolating an Expression or a Constant to the same vector space as u lives in (V).

In the code above we demonstrate how to use

numpy functionality to compute the norm of

the difference between the two most recent solutions. Here we apply

the maximum norm ( norm) on the difference of the solution vectors

(ord=1 and ord=2 give the

norm) on the difference of the solution vectors

(ord=1 and ord=2 give the  and

and  vector

norms – other norms are possible for numpy arrays,

see pydoc numpy.linalg.norm).

vector

norms – other norms are possible for numpy arrays,

see pydoc numpy.linalg.norm).

The file picard_np.py contains the complete code for

this nonlinear Poisson problem.

The implementation is  dimensional, with mesh

construction and setting of Dirichlet conditions as explained in

the section Parameterizing the Number of Space Dimensions.

For a

dimensional, with mesh

construction and setting of Dirichlet conditions as explained in

the section Parameterizing the Number of Space Dimensions.

For a  grid with

grid with  we need 9 iterations for convergence

when the tolerance is

we need 9 iterations for convergence

when the tolerance is  .

.

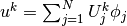

After having discretized our nonlinear PDE problem, we may

use Newton’s method to solve the system of nonlinear algebraic equations.

From the continuous variational problem,

the discrete version results in a

system of equations for the unknown parameters

(7)

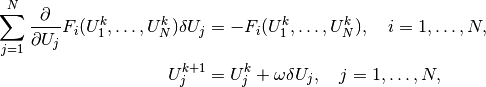

Newton’s method for the system  ,

,  can be formulated as

can be formulated as

where ![\omega\in [0,1]](_images/math/c918e3e2e228f3ed67d74bcf2a5cda9c4aabfa48.png) is a relaxation parameter, and

is a relaxation parameter, and  is

an iteration index. An initial guess

is

an iteration index. An initial guess  must

be provided to start the algorithm.

must

be provided to start the algorithm.

The original Newton method has  , but in problems where it is

difficult to obtain convergence,

so-called under-relaxation with

, but in problems where it is

difficult to obtain convergence,

so-called under-relaxation with  may help. It means that

one takes a smaller step than what is suggested by Newton’s method.

may help. It means that

one takes a smaller step than what is suggested by Newton’s method.

We need, in a program, to compute the Jacobian

matrix  and the right-hand side vector

and the right-hand side vector  .

Our present problem has

.

Our present problem has  given by above.

The derivative

given by above.

The derivative  becomes

becomes

(8)

The following results were used to obtain the previous equation:

We can reformulate the Jacobian matrix

by introducing the short

notation  :

:

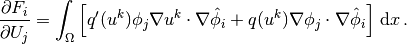

In order to make FEniCS compute this matrix, we need to formulate a corresponding variational problem. Looking at the linear system of equations in Newton’s method,

we can introduce  as a general test function replacing

as a general test function replacing  ,

and we can identify the unknown

,

and we can identify the unknown

. From the linear system

we can now go “backwards” to construct the corresponding linear

discrete weak form to be solved in each Newton iteration:

. From the linear system

we can now go “backwards” to construct the corresponding linear

discrete weak form to be solved in each Newton iteration:

(9)

This variational form fits the standard notation

with

with

Note the important feature in Newton’s method

that the

previous solution  replaces

replaces  in the formulas when computing the matrix

in the formulas when computing the matrix

and vector

and vector  for the linear system in

each Newton iteration.

for the linear system in

each Newton iteration.

We now turn to the implementation.

To obtain a good initial guess  , we can solve a simplified, linear

problem, typically with

, we can solve a simplified, linear

problem, typically with  , which yields the standard Laplace

equation

, which yields the standard Laplace

equation  . The recipe for solving this problem

appears in the sections Variational Formulation,

Implementation (1), and Combining Dirichlet and Neumann Conditions.

The code for computing

. The recipe for solving this problem

appears in the sections Variational Formulation,

Implementation (1), and Combining Dirichlet and Neumann Conditions.

The code for computing  becomes as follows:

becomes as follows:

tol = 1E-14

def left_boundary(x, on_boundary):

return on_boundary and abs(x[0]) < tol

def right_boundary(x, on_boundary):

return on_boundary and abs(x[0]-1) < tol

Gamma_0 = DirichletBC(V, Constant(0.0), left_boundary)

Gamma_1 = DirichletBC(V, Constant(1.0), right_boundary)

bcs = [Gamma_0, Gamma_1]

# Define variational problem for initial guess (q(u)=1, i.e., m=0)

u = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

a = inner(grad(u), grad(v))*dx

f = Constant(0.0)

L = f*v*dx

A, b = assemble_system(a, L, bcs)

u_k = Function(V)

U_k = u_k.vector()

solve(A, U_k, b)

Here, u_k denotes the solution function for the previous

iteration, so that the solution

after each Newton iteration is u = u_k + omega*du.

Initially, u_k is the initial guess we call  in the mathematics.

in the mathematics.

The Dirichlet boundary conditions for  , in

the problem to be solved in each Newton

iteration, are somewhat different than the conditions for

, in

the problem to be solved in each Newton

iteration, are somewhat different than the conditions for  .

Assuming that

.

Assuming that  fulfills the

Dirichlet conditions for

fulfills the

Dirichlet conditions for  ,

,  must be zero at the boundaries

where the Dirichlet conditions apply, in order for

must be zero at the boundaries

where the Dirichlet conditions apply, in order for  to fulfill

the right boundary values. We therefore define an additional list of

Dirichlet boundary conditions objects for

to fulfill

the right boundary values. We therefore define an additional list of

Dirichlet boundary conditions objects for  :

:

Gamma_0_du = DirichletBC(V, Constant(0), left_boundary)

Gamma_1_du = DirichletBC(V, Constant(0), right_boundary)

bcs_du = [Gamma_0_du, Gamma_1_du]

The nonlinear coefficient and its derivative must be defined before coding the weak form of the Newton system:

def q(u):

return (1+u)**m

def Dq(u):

return m*(1+u)**(m-1)

du = TrialFunction(V) # u = u_k + omega*du

a = inner(q(u_k)*grad(du), grad(v))*dx + \

inner(Dq(u_k)*du*grad(u_k), grad(v))*dx

L = -inner(q(u_k)*grad(u_k), grad(v))*dx

The Newton iteration loop is very similar to the Picard iteration loop in the section Picard Iteration:

du = Function(V)

u = Function(V) # u = u_k + omega*du

omega = 1.0 # relaxation parameter

eps = 1.0

tol = 1.0E-5

iter = 0

maxiter = 25

while eps > tol and iter < maxiter:

iter += 1

A, b = assemble_system(a, L, bcs_du)

solve(A, du.vector(), b)

eps = numpy.linalg.norm(du.vector().array(), ord=numpy.Inf)

print 'Norm:', eps

u.vector()[:] = u_k.vector() + omega*du.vector()

u_k.assign(u)

There are other ways of implementing the update of the solution as well:

u.assign(u_k) # u = u_k

u.vector().axpy(omega, du.vector())

# or

u.vector()[:] += omega*du.vector()

The axpy(a, y) operation adds a scalar a times a Vector y to a Vector object. It is usually a fast operation calling up an optimized BLAS routine for the calculation.

Mesh construction for a $d$-dimensional problem with arbitrary degree of the Lagrange elements can be done as explained in the section Parameterizing the Number of Space Dimensions. The complete program appears in the file alg_newton_np.py.

Although Newton’s method in PDE problems is normally formulated at the linear algebra level, i.e., as a solution method for systems of nonlinear algebraic equations, we can also formulate the method at the PDE level. This approach yields a linearization of the PDEs before they are discretized. FEniCS users will probably find this technique simpler to apply than the more standard method in the section A Newton Method at the Algebraic Level.

Given an approximation to the solution field,  , we seek a

perturbation

, we seek a

perturbation  so that

so that

fulfills the nonlinear PDE.

However, the problem for  is still nonlinear and nothing is

gained. The idea is therefore to assume that

is still nonlinear and nothing is

gained. The idea is therefore to assume that  is sufficiently

small so that we can linearize the problem with respect to

is sufficiently

small so that we can linearize the problem with respect to  .

Inserting

.

Inserting  in the PDE,

linearizing the

in the PDE,

linearizing the  term as

term as

and dropping nonlinear terms in  ,

we get

,

we get

We may collect the terms with the unknown  on the left-hand side,

on the left-hand side,

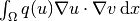

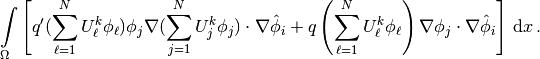

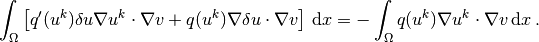

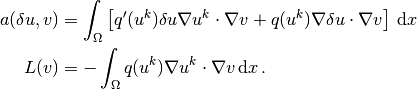

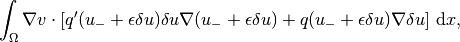

The weak form of this PDE is derived by multiplying by a test function  and integrating over

and integrating over  , integrating as usual

the second-order derivatives by parts:

, integrating as usual

the second-order derivatives by parts:

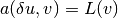

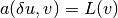

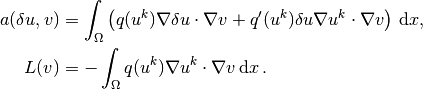

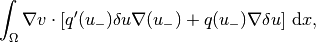

The variational problem reads: find  such that

such that

for all

for all  , where

, where

The function spaces  and

and  , being continuous or discrete,

are as in the

linear Poisson problem from the section Variational Formulation.

, being continuous or discrete,

are as in the

linear Poisson problem from the section Variational Formulation.

We must provide some initial guess, e.g., the solution of the

PDE with  . The corresponding weak form

. The corresponding weak form  has

has

Thereafter, we enter a loop and solve

for

for  and compute a new approximation

and compute a new approximation

. Note that

. Note that  is a correction, so if

is a correction, so if

satisfies the prescribed

Dirichlet conditions on some part

satisfies the prescribed

Dirichlet conditions on some part  of the boundary,

we must demand

of the boundary,

we must demand  on

on  .

.

Looking at the equations just derived,

we see that the variational form is the same as for the Newton method

at the algebraic level in the section A Newton Method at the Algebraic Level. Since Newton’s method at the

algebraic level required some “backward” construction of the

underlying weak forms, FEniCS users may prefer Newton’s method at the

PDE level, which this author finds more straightforward, although not so

commonly documented in the literature on numerical methods for PDEs.

There is seemingly no need for differentiations to derive a Jacobian

matrix, but a mathematically equivalent derivation is done when

nonlinear terms are linearized using the first two Taylor series terms

and when products in the perturbation  are neglected.

are neglected.

The implementation is identical to the one in the section A Newton Method at the Algebraic Level and is found in the file pde_newton_np.py. The reader is encouraged to go through this code to be convinced that the present method actually ends up with the same program as needed for the Newton method at the linear algebra level in the section A Newton Method at the Algebraic Level.

The previous hand-calculations and manual implementation of Picard or Newton methods can be automated by tools in FEniCS. In a nutshell, one can just write

problem = NonlinearVariationalProblem(F, u, bcs, J)

solver = NonlinearVariationalSolver(problem)

solver.solve()

where F corresponds to the nonlinear form  ,

u is the unknown Function object, bcs

represents the essential boundary conditions (in general a list of

DirichletBC objects), and

J is a variational form for the Jacobian of F.

,

u is the unknown Function object, bcs

represents the essential boundary conditions (in general a list of

DirichletBC objects), and

J is a variational form for the Jacobian of F.

Let us explain in detail how to use the built-in tools for nonlinear variational problems and their solution. The appropriate F form is straightforwardly defined as follows, assuming q(u) is coded as a Python function:

u_ = Function(V) # most recently computed solution

v = TestFunction(V)

F = inner(q(u_)*grad(u_), grad(v))*dx

Note here that u_ is a Function (not a TrialFunction).

An alternative and perhaps more intuitive formula for  is to

define

is to

define  directly in terms of

a trial function for

directly in terms of

a trial function for  and a test function for

and a test function for  , and then

create the proper F by

, and then

create the proper F by

u = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

F = inner(q(u)*grad(u), grad(v))*dx

u_ = Function(V) # the most recently computed solution

F = action(F, u_)

The latter statement is equivalent to  , where

, where  is

an existing finite element function representing the most recently

computed approximation to the solution.

(Note that

is

an existing finite element function representing the most recently

computed approximation to the solution.

(Note that  and

and  in the previous notation

correspond to

in the previous notation

correspond to  and

and  in the present

notation. We have changed notation to better align the mathematics with

the associated UFL code.)

in the present

notation. We have changed notation to better align the mathematics with

the associated UFL code.)

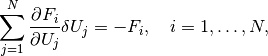

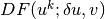

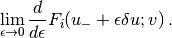

The derivative  (J) of

(J) of  (F) is formally the

Gateaux derivative

(F) is formally the

Gateaux derivative  of

of  at

at  in the direction of

in the direction of  .

Technically, this Gateaux derivative is derived by computing

.

Technically, this Gateaux derivative is derived by computing

(10)

The  is now the trial function and

is now the trial function and  is the previous

approximation to the solution

is the previous

approximation to the solution  .

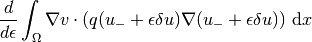

We start with

.

We start with

and obtain

which leads to

as  .

This last expression is the Gateaux derivative of

.

This last expression is the Gateaux derivative of  . We may use

. We may use  or

or

for this derivative, the latter having the advantage

that we easily recognize the expression as a bilinear form. However, in

the forthcoming code examples J is used as variable name for

the Jacobian.

for this derivative, the latter having the advantage

that we easily recognize the expression as a bilinear form. However, in

the forthcoming code examples J is used as variable name for

the Jacobian.

The specification of J goes as follows if du is the TrialFunction:

du = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

u_ = Function(V) # the most recently computed solution

F = inner(q(u_)*grad(u_), grad(v))*dx

J = inner(q(u_)*grad(du), grad(v))*dx + \

inner(Dq(u_)*du*grad(u_), grad(v))*dx

The alternative specification of F, with u as TrialFunction, leads to

u = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

u_ = Function(V) # the most recently computed solution

F = inner(q(u)*grad(u), grad(v))*dx

F = action(F, u_)

J = inner(q(u_)*grad(u), grad(v))*dx + \

inner(Dq(u_)*u*grad(u_), grad(v))*dx

The UFL language, used to specify weak forms, supports differentiation of forms. This feature facilitates automatic symbolic computation of the Jacobian J by calling the function derivative with F, the most recently computed solution (Function), and the unknown (TrialFunction) as parameters:

du = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

u_ = Function(V) # the most recently computed solution

F = inner(q(u_)*grad(u_), grad(v))*dx

J = derivative(F, u_, du) # Gateaux derivative in dir. of du

or

u = TrialFunction(V)

v = TestFunction(V)

u_ = Function(V) # the most recently computed solution

F = inner(q(u)*grad(u), grad(v))*dx

F = action(F, u_)

J = derivative(F, u_, u) # Gateaux derivative in dir. of u

The derivative function is obviously very convenient in problems where differentiating F by hand implies lengthy calculations.

The preferred implementation of F and J, depending on whether du or u is the TrialFunction object, is a matter of personal taste. Derivation of the Gateaux derivative by hand, as shown above, is most naturally matched by an implementation where du is the TrialFunction, while use of automatic symbolic differentiation with the aid of the derivative function is most naturally matched by an implementation where u is the TrialFunction. We have implemented both approaches in two files: vp1_np.py with u as TrialFunction, and vp2_np.py with du as TrialFunction. The directory stationary/nonlinear_poisson contains both files. The first command-line argument determines if the Jacobian is to be automatically derived or computed from the hand-derived formula.

The following code defines the nonlinear variational problem and an associated solver based on Newton’s method. We here demonstrate how key parameters in Newton’s method can be set, as well as the choice of solver and preconditioner, and associated parameters, for the linear system occurring in the Newton iteration.

problem = NonlinearVariationalProblem(F, u_, bcs, J)

solver = NonlinearVariationalSolver(problem)

prm = solver.parameters

prm['newton_solver']['absolute_tolerance'] = 1E-8

prm['newton_solver']['relative_tolerance'] = 1E-7

prm['newton_solver']['maximum_iterations'] = 25

prm['newton_solver']['relaxation_parameter'] = 1.0

if iterative_solver:

prm['linear_solver'] = 'gmres'

prm['preconditioner'] = 'ilu'

prm['krylov_solver']['absolute_tolerance'] = 1E-9

prm['krylov_solver']['relative_tolerance'] = 1E-7

prm['krylov_solver']['maximum_iterations'] = 1000

prm['krylov_solver']['gmres']['restart'] = 40

prm['krylov_solver']['preconditioner']['ilu']['fill_level'] = 0

set_log_level(PROGRESS)

solver.solve()

A list of available parameters and their default values can as usual be printed by calling info(prm, True). The u_ we feed to the nonlinear variational problem object is filled with the solution by the call solver.solve().